From extraction to enterprise: How local firms can ride the mining-tech wave

From Ounces to Opportunity

Ghana has re-emerged as Africa’s leading gold producer, and its upward trajectory shows no signs of slowing. National output is expected to reach 5.1 million ounces in 2025, exceeding the record 4.8 million ounces in 2024, driven by steady performance in large-scale mines and renewed momentum in artisanal production.

In value terms, the sector delivered a remarkable shift: gold export earnings surged by more than 50 percent in 2024, reaching an estimated US $11.6 billion, of which nearly US $5 billion came from legal small-scale operators.

But the central development question is no longer about sheer output. It is about retention, transformation, and participation. How much of the mining value chain remains within Ghana? How deeply does that value circulate through domestic enterprises? And crucially, can Ghanaian firms position themselves at the frontier of a rapidly evolving “mining-tech” ecosystem built around drones, sensors, artificial intelligence, geospatial analytics, and real-time data services?

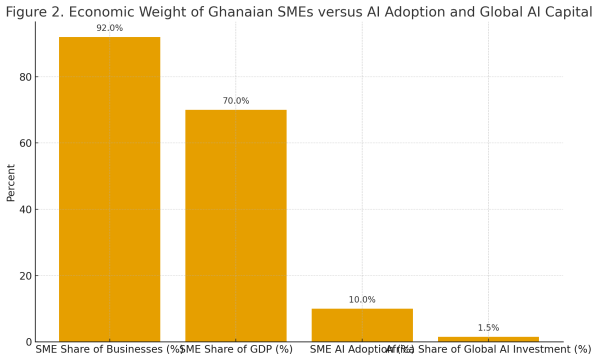

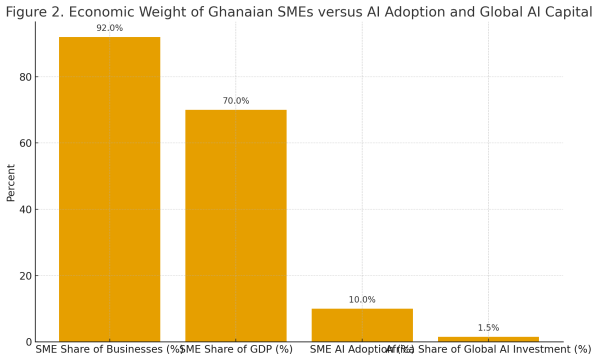

Small and medium-sized enterprises sit at the heart of this opportunity. Peer-reviewed studies and national statistical records converge on the same conclusion: SMEs represent roughly 92 percent of registered businesses, contribute about 70 percent of Ghana’s GDP, and account for up to 80 percent of total employment. If mining-tech is to move from a niche capability to a national growth engine, it will be because Ghanaian SMEs become the architects, suppliers, and innovators within this emerging landscape—not passive observers standing at its margins.

Mining Revenues, Local Procurement, and the Missing Link

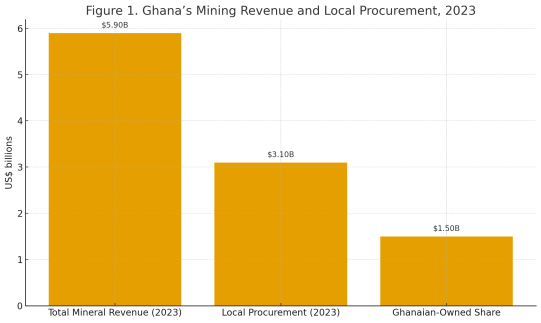

Recent data indicate that Ghana is beginning to retain a greater share of mining revenue. In 2023, members of the Ghana Chamber of Mines spent approximately US $3.1 billion on goods and services sourced locally, representing about 53 percent of the sector’s total mineral revenue of US $5.9 billion. The Chamber further estimates that in 2024, roughly US $5.5 billion, or 74 percent of total receipts, was retained in the domestic economy through procurement, taxes, wages, and community-level investment.

Yet official procurement records reveal a more complex landscape. According to the Sixth Edition of the Minerals Commission’s Local Procurement List, only about half of the US $3 billion spent on mining goods and services in 2023 went to companies whose shareholders and directors are Ghanaian nationals. Put differently, although the volume of local sourcing is rising, a significant portion of the supply chain remains dominated by foreign-owned service providers operating within Ghana’s borders.

This should not be interpreted as a failure but rather as evidence of untapped space for domestic enterprise growth. It signals that Ghanaian firms have room to climb the supply-chain ladder, from low-value services into higher-value, more technologically intensive roles that can anchor long-term industrial capability

Ghana’s Local Content and Local Participation Regulations, L.I. 2431 (2020), were crafted to narrow precisely this gap. The framework obliges mineral right holders and their principal contractors to hire Ghanaians, source designated goods and services locally, and file detailed localization and annual content reports with the Minerals Commission.

The policy intent is unambiguous: to ensure that the mining economy generates domestic value rather than merely domestic activity. The real test, however, lies in whether Ghanaian firms can scale the technical capabilities required to meet this demand, particularly as mining shifts toward digital, automated and AI-enabled operations.

The global mining-tech wave and Africa’s position

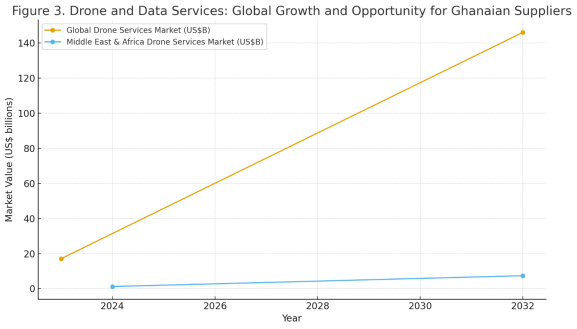

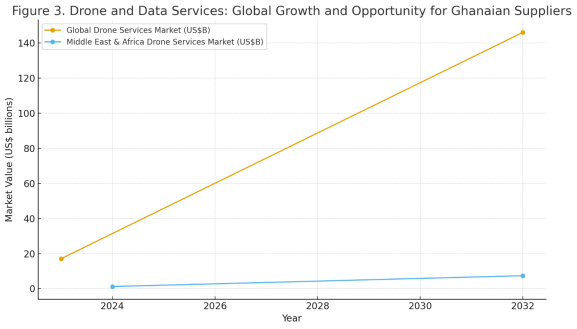

Globally, data-driven automation is transforming how mines are planned, operated and rehabilitated. Market estimates indicate that the global drone services industry — spanning surveying, mapping and environmental monitoring — was valued at approximately 17.1 billion US dollars in 2023 and is projected to surpass 146 billion US dollars by 2032, representing a compound annual growth rate of more than 27 percent.

Environmental-monitoring applications, including water-quality assessment, tailings surveillance and land-restoration tracking, are among the fastest-expanding segments, with several forecasts pointing to annual growth rates above 30 percent.

Africa is participating in this expansion, though from a comparatively modest base. The continent’s drone market was valued at about 1 billion US dollars in 2024 and is expected to grow to roughly 9.3 billion US dollars by 2033. Across the broader Middle East and Africa region, drone services alone were estimated at approximately 1.25 billion US dollars in 2024, with projections exceeding 7.4 billion US dollars by 2032. Mining and construction remain major drivers of this demand.

Artificial intelligence investment, however, highlights a more pronounced divide between advanced and developing economies. The 2025 Stanford AI Index reports that private AI investment in the United States reached an estimated 109 billion US dollars in 2024 — nearly twelve times China’s 9.3 billion US dollars, and far beyond cumulative investment levels across emerging markets.

Recent analyses show that Africa accounts for only around 1 to 1.5 percent of global AI expenditure, despite accelerating adoption. In one recent quarter, African start-ups attracted as little as 0.02 to 0.03 percent of worldwide AI funding, even as global AI venture investment surpassed 47 billion US dollars.

Ghana therefore confronts a dual reality: it is situated within a region experiencing rapid growth in drone and data services, where mining companies are already deploying AI-enabled drones to address illegal mining and environmental risk; yet it also competes in a global AI landscape where capital, talent and intellectual property remain heavily concentrated in North America, Europe and parts of Asia.

Ghanaian SMEs at the frontier of mining-tech

This global imbalance does not mean Ghanaian firms are excluded from the mining-tech opportunity; rather, it reshapes where their competitive edge is likely to emerge. Ghana’s strengths lie not in building foundational AI models—where capital, compute power, and research depth are heavily concentrated in advanced economies—but in applied innovation: adapting proven AI tools to local geology, regulatory requirements, and the complex field conditions that define West African mining.

Recent policy experience shows the potential of this approach. The “Enhancing Local Procurement in Mining” initiative, implemented with international partners, has supported mining companies and domestic suppliers since 2022 to raise local sourcing, strengthen technical capabilities, and integrate more Ghanaian firms into the upstream supply chain. To date, the programme reports facilitating more than 800 jobs and enabling over 900 Ghanaian contractors to participate in mining procurement, particularly in engineering, logistics, and maintenance.

Research makes clear how central SMEs are to Ghana’s economic structure. They represent roughly 92 percent of registered businesses, contribute about 70 percent of GDP, and sustain the majority of employment. Yet, by 2023, fewer than one in ten had integrated any form of AI into their operations.

This adoption gap is not merely a constraint but one of Ghana’s largest untapped opportunities. With targeted digital skilling, access to appropriate technologies, and sector-specific support, SMEs could become the backbone of the country’s transition into data-enabled, mining-tech driven growth.

Closing that gap in the mining-tech context means helping Ghanaian enterprises to specialize in areas where they can combine local presence with frontier tools. Examples include:

- Drone fleet operation, maintenance and repair in remote mining districts

- Geospatial data annotation and model training that reflect Ghana’s specific terrain, vegetation and river systems

- Software services that integrate AI alerts with Ghana’s licensing, local content and environmental regulations

- Local manufacture and assembly of selected equipment on the Minerals Commission procurement list, from pipe fittings to basic sensor housings, which can gradually move into more complex components.

From local procurement to local manufacturing

Ghana’s policy debate is already moving in this direction. Earlier this year, the Chief Executive Officer of the Ghana Chamber of Mines urged a shift beyond local procurement toward genuine local manufacturing within the mining supply chain, a transition aimed at building an equipment and services ecosystem capable of meeting domestic demand and competing internationally.

The data underline the opportunity. The Minerals Commission reports that of the roughly 3 billion US dollars spent on mining goods and services in 2023, only about half accrued to firms owned by Ghanaian nationals. Even a modest reallocation of the remaining expenditure toward domestic producers and service providers would have outsized effects on SME expansion, technology upgrading, and job creation.

For Ghanaian enterprises, the strategic question is how to use mining demand as a springboard. Firms that become proficient in mine-site monitoring, water quality analysis and rehabilitation planning for Tarkwa, Obuasi or Bibiani can sell similar services to clients in Burkina Faso or Côte d’Ivoire. In this sense, local content policy is not only an industrial policy for Ghana. It is a potential export strategy for the subregion.

Comparative lessons and the road ahead

Advanced mining jurisdictions such as Canada and Australia have already shown that strong local supplier ecosystems grow around mines that demand high standards for safety, environmental performance and digital monitoring.

Studies of digital transformation in mining describe how South African producers are using autonomous vehicles and AI-based safety systems, while Ghanaian operations are beginning to deploy sensors and Internet of Things platforms to track environmental and safety conditions in real time.

The lesson for Ghana is not to copy the exact technology mix of richer countries. It is to adapt the underlying logic. That logic links clear regulation, demanding buyers, and capable local suppliers in a reinforcing loop.

For policy makers, this means consistent enforcement of local content rules, support for supplier development programmes, and targeted financing for SMEs that invest in mining-tech capabilities. For enterprises, it means moving beyond trading imported equipment into mastering design, integration and after-sales service. For universities and training centres, it means aligning curricula in geospatial analysis, data science and engineering with the skills that mining-tech firms actually require.

For Ghana’s development partners and global investors, it is a reminder that the most transformative AI and drone investments in a country like Ghana are not necessarily those that chase the latest research breakthroughs. They are those that build durable local capability to apply existing tools in ways that protect rivers, create decent work and open regional markets.

Conclusion: From mineral boom to enterprise dividend

In the first part of this series, the focus was on mining reforms that can turn gold receipts into national resilience. In the second part, the spotlight shifted to AI, drones and satellites that can help end the devastation of galamsey and restore Ghana’s rivers.

This final part has argued that the story will remain incomplete unless Ghanaian enterprises occupy the centre of the mining-tech value chain. SMEs already contribute close to 70 percent of Ghana’s GDP and more than 90 percent of its businesses.

If they are equipped to supply, innovate and export within a rapidly growing global market for drone, data and environmental services, then mining can become not only a source of foreign exchange but a platform for technological upgrading and enterprise growth.

The choice is not between minerals and manufacturing, or between environmental protection and entrepreneurship. It is whether Ghana can design and execute a strategy that links all three. If it does, the same technologies that now watch over rivers from above can help build companies on the ground that create value long after the last ounce of ore has been extracted.

Joseph is a visionary entrepreneur, business development consultant, and philanthropist based in the United States. With a global network spanning renowned companies, he is deeply committed to fostering innovation and strategic growth across industries.